Step outside for a nature walk and you’re likely to encounter invasive plants—barberry and burning bush, to name just two that are fast encroaching on Northeast woodlands. But you may be surprised to learn that there are nurseries and online plant stores selling these self-same invasive plants. Evelyn Beaury, a scientist and assistant curator at the New York Botanical Garden’s Center for Conservation and Restoration Ecology, has been studying the effects of the nursery trade on invasive plant spread. “About 60 percent of plants we’ve recognized as invasive are still being sold through commercial nursery trade in the U.S.,” she says. And as a result, people are still buying and planting them in their gardens. We talked with Beaury to explain why we should be concerned about this and what we can all do to slow the spread of invasives.

What is an invasive plant anyway? An invasive plant, according to Beaury, is one “introduced to an area by humans—it wouldn’t have gotten there on its own—and has spread rapidly, causing measurable negative socioeconomic or ecological impacts.” About half of the species that are considered invasives today were intentionally brought to the U.S. for ornamental, agricultural, medicinal, and other plant trade purposes.

“Invasive plants can dominate an ecosystem,” says Beaury. Their leaves and seeds can be toxic to wildlife. They can outcompete native plants. And they can completely alter the terrain: clogging up waterways or transforming forest structures from closed to open canopy. Stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum), for example, is proliferating on the East Coast, notes Beaury. It creates dense mats of vegetation that cover the forest floor, which prevents native tree seedlings from taking root. Cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) on the West Coast is doing the same thing, turning the forest into grassland. “If those invasive species come in first, it’s really hard for native species to recruit seedlings,” she says. When these plants out-compete native ones, they decrease the diversity of an ecosystem. And all these changes harm the wildlife that rely on plants they co-evolved with for food and shelter.

There are also financial consequences. The control of invasive species in the U.S. costs an estimated $20 billion, not to mention the environmental and health damage that many of the controls themselves (such as the use of herbicides) cause. Invasive species can diminish property values as well—who wants to buy a house with an infestation of knotweed? “The big thing with invasives is that they’re just making all of our other issues with land management more challenging and more expensive,” says Beaury. We need to be proactive since it’s so much harder to deal with an infestation than to stop one before it starts.

Here’s what you can do:

If you see something, say something.

Invasive species bans are not always enforced at nurseries. It’s up to consumers to take action. If you see something (a barberry for sale, for instance), say something. Talk to your nursery about the problems with invasives. Recommend they consult invasive species lists (see below) if they’re uninformed and encourage them to stock more native plants. Ask them not to sell invasives—and keep asking until they stop. Tell your friends. Post on social media. Talk to your elected officials. Consumers have power. Bees, butterflies, birds, and other wildlife need all of us!

Non-native Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii) is still available in the nursery trade and has spread rapidly in woodlands where it is outcompeting vital native species. Plus, it supports blacklegged ticks, which harbor Lyme disease, by creating humid microclimates preferred by them. Photograph by Calin Darabus.

Think beyond your local area.

As our climate changes, so does the range of where invasives grow. Certain non-native plants that were traditionally considered invasive in, say, Virginia, are now creeping north as our winters warm. “We’ve been advocating for thinking more regionally rather than by county or state,” says Beaury. Just because a plant isn’t a designated invasive in your state doesn’t mean it isn’t. “A lot of our invasive species problems in New England are similar to the problems folks are dealing with in other regions, such as similar species of concern in parts of Oregon and Washington,” she says. The best way to stop the spread is by not planting them. Beaury suggests playing it safe: Do not buy non-native plants considered invasive anywhere in the U.S., even if they’re technically allowed in your state. Check out USDA invasive lists and avoid buying any non-native plant described as aggressive or is known to spread rapidly.

Your choices matter—really, they do.

If you’re thinking: how’s one plant really going to cause a problem, just look at burning bush (Euonymus alatus). One burning bush shrub produces tens of thousands of seeds a year, which are then spread by rain, birds, and other critters. Tens of thousands of seeds! But on the flip side, growing native plants in a small yard makes a huge difference to the wildlife, like native bees, butterflies, birds, that desperately need them. Native oak trees support more than 900 species of moths and butterflies. Monarchs can’t survive without milkweed. Ruby-throated hummingbirds love the native Eastern red columbine and coral honeysuckle.

“Knotweed is a riparian invader, which means it spreads along stream banks, causing huge amounts of erosion and preventing animals from accessing water. It also degrades the soil and can grow in crazy places,” says Beaury, who snapped this photograph of knotweed growing through concrete.

Photograph by Evelyn Beaury.

When in doubt, grow native plants.

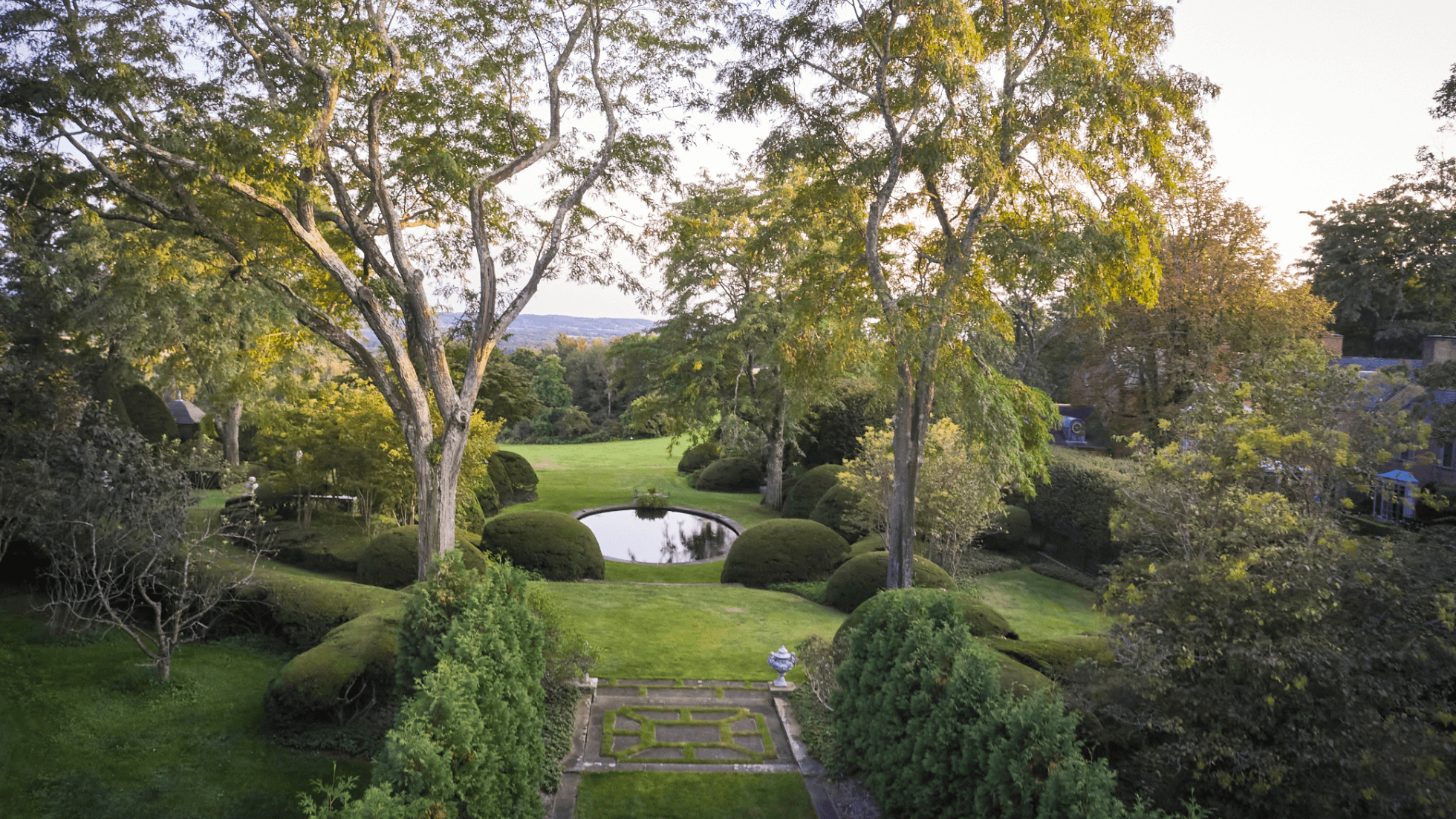

Approximately 80 percent of ornamental plants at the nursery are not native. But while not all non-native plants are invasive, they’re 40 times more likely to become so. Since we don’t really know how a non-native plant will behave in a new and changing environment, Beaury recommends we all opt for native plants first. And here’s the good news, there are so many beautiful ones on the market now, with more becoming available in nurseries as more gardeners discover their beauty and usefulness. In 2021, one in four people specifically bought native plants to grow in their yards. Contact your local native plant society, order from native seed and plant nurseries (see our story: Where Do the Pros Go to Source Native Plants), and check out public gardens and organizations dedicated to them, like the Native Plant Trust, Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, Theodore Payne Foundation, Mt. Cuba Center, and Stoneleigh, to learn more.

“I’m feeling more and more optimistic,” says Beaury. “We’re seeing people buy more native plants, be thoughtful about the way they’re managing landscapes, and put more resources into doing all of that strategically,” she says. “And we’re seeing more and more success stories about people removing invasives and restoring native ecosystems.” It’s up to us.

To learn more about Beaury’s research on invasives, click here. Click here to read the native plant alternatives to common invasive nursery plants selected by experts and designers.

Read more on our series about invasive plants:

Discover 12 fabulous native plant alternatives to common invasive plants.

Learn 7 ways to reduce invasive plants without chemicals.

By Melissa Ozawa

This is part of a series with Gardenista, which ran on February 20, 2025.