By Laura Fenton

Photos by Ngoc Minh Ngo, unless otherwise noted

It’s no secret that biodiversity is in decline: North America has lost close to 3 billion birds since the 1970s, and insects are disappearing just as quickly. More than a third of plants are also at risk of extinction. A gloomy picture, to say the least, but unlike much of the bad news about the climate crisis, this is one area in which we can make a difference. By changing the way we garden, our own backyards can provide critical food and shelter for birds, butterflies, and all kinds of tiny invertebrates critical to soil health.

Once we stop using pesticides and start planting more native plants, we’re on the path to creating more biodiversity, but if you want to go further, you need to get to know what is living in your landscape. “It can make you more aware of what’s out there,” says Jennifer Hopwood, a Senior Pollinator Conservation Specialist with the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. “When you start to look for the little small things, there’s so much life in your space.” Conducting a biodiversity audit of the flora and fauna living in your yard will arm you with knowledge that can help you manage your landscape in even more wildlife-friendly ways, Hopwood adds, whether that’s planting more host plants for butterflies or planting more native plants to support insects to feed your favorite songbirds. You’ll also be more in tune with your land once you can name the life that is thriving there. For example, when I first saw ghost pipe (Monotropa uniflora L.) in my yard, I confess I thought, “Ew, weird mushroom,” but I’ve since learned it is a parasitic plant that is thought of as an indicator of a healthy ecosystem: I’m now proud and protective of what I once thought was yucky.

A biodiversity audit can also be more than a personal project: Scientists regularly call on community members to share their observations for participatory projects online. The Great Backyard Bird Count, a project started by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and National Audubon Society, is perhaps the best known example, as it was the first community-science project. Every February people across the globe collect data on wild birds at the same time, which helps conservationists track their numbers and distribution.

If you’re lucky you might discover something rare while auditing your yard. When the famed English garden Great Dixter conducted a biodiversity audit, they discovered two endangered mining bee species, the white-bellied mining bee (Andrena gravida) and oak-mining bee (Andrena ferox), and rare purple emperor butterfly (Apatura iris) among the 2,029 species recorded. And once you know what you’ve got, you can actively work to support and protect it. For example, when master forager Tama Matsuoka Wong, who is the author of Into the Weeds: How to Garden Like a Forager, worked with a local wildflower preserve to conduct a plant audit on her property, each plant was given a coefficient of conservatism score (basically its range of ecological tolerance, with a high score meaning it is found in only a narrow range of habitats). Wong says, “Those numbers were really helpful, for me. I would be like, Oh, well, if that’s going to be a five or above, I’m going to cage it.” Wong also removed invasive plants like Japanese honeysuckle surrounding special plants. (You can find New York’s C-values here and download the Northeast Regional Floristic Quality Assessment here.) Likewise, if you spotted a zebra swallowtail (Protographium marcellus) and hoped to see more in the future, like I have, you might decide to plant some of its host plant, the pawpaw tree (Asimina triloba).

Here’s how to audit the wildlife in your own backyard.

Divide your yard into “habitats”

In order to discover what parts of your landscape are supporting the most wildlife, it can be helpful to audit it one section at a time. These can be loosely defined zones, like “front lawn,” “wooded area,” “cut flower bed,” and “foliage bed by patio.” Your findings may surprise you: Great Dixter, for example, discovered that its ornamental garden–not the woodlands or meadows–had the greatest biodiversity.

Download some apps

In today’s age of plant and animal identification apps, it’s easier than ever to identify what creatures are in your yard. Apps are by no means perfect, but they are easy to use and can be a great aid in your auditing. For birds, Cornell Lab’s Merlin Bird ID app offers a step-by-step process to identify unknown birds. PictureThis and its sister apps PictureInsect and PictureMushroom, use AI to analyze your photo and suggest a possible ID, as does Seek by iNaturalist. iNaturalist is the most common app of choice for bioblitzes and community science projects. Bee Machine is a relative newcomer from Kansas State University that focuses on, well, bees. If you get deep into IDing bugs, a clip-on macro lens for your smartphone can help you get better pictures of tiny creatures.

Wong plants mountain mint because of its benefits to insects, especially native bees, butterflies, and wasps.

Crack open a spreadsheet

You can certainly record your findings with pen and paper, but if you want to get nerdy (and here at Perfect Earth Project we are all about getting nerdy) a spreadsheet can help you keep your findings organized. You can also create a new spreadsheet or additional columns each year to compare year-over-year observations. “Over time, it’s easy to forget,” says Wong. “So it’s interesting to create a kind of snapshot in time, to see the trajectory of what’s happening.”

Start big

Trying to catalog every single creature on your property is practically impossible. “It can get overwhelming so quickly because in your yard there can be a hundred or more types of invertebrates alone,” says Hopwood. So, start with the largest creatures and plants and then work your way down. You can probably tick off a list of every mammal you’ve seen in your yard right now, ditto the biggest birds, and IDing all the trees won’t take long with the help of an app or a local field guide.

Follow Your Interests

Once you start narrowing in on smaller species, like say sedges rather than trees, or bees rather than amphibians, focus on your personal interests, says Hopwood. “If you really love flowers, you might want to choose pollinators,” she says; likewise, if you are an avid vegetable gardener, you might start with everything living in your raised beds. If you love birds, go deep there.

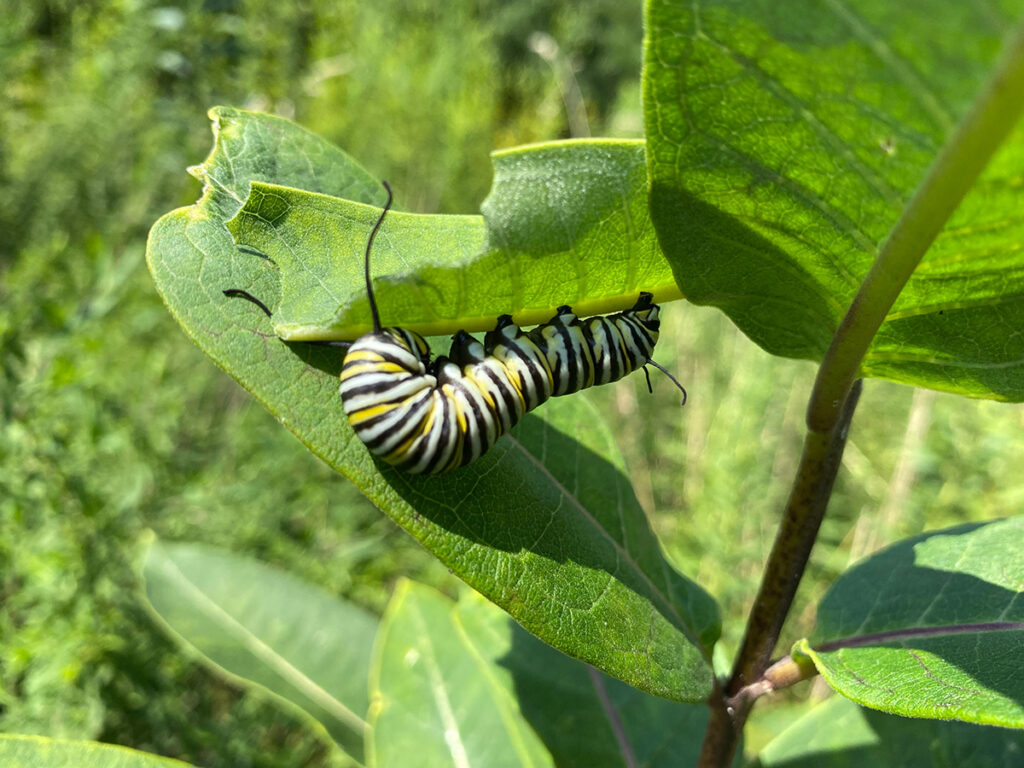

Monarch caterpillars need milkweed leaves to survive. If you love butterflies, plant some milkweed in your garden and be on the lookout for them. They will come! Photo by Eric Ozawa

Get to Know the Bugs

Hopwood emphasizes the value of sharing your findings with community scientist projects, pointing to the Bumblebee Watch, a project that the Xerces Society has collaborated on, as an example. “We know that about 28-percent of bumblebees in North America are at risk of extinction,” she says. “It’s really been helpful for identifying some of those imperial species, where they’re hanging on and where they’re not.” iNaturalist has local projects posted on their site and app, and your local conservation group may run projects, as well.

Don’t Sweat the Details

Both Wong and Hopwood emphasize that even experts can’t always identify a species without the help of a microscope, but that shouldn’t discourage you from trying. “You can still identify it at the genus level and that can tell you something about its biology, where it lives, what time of year you can find it,” says Hopwood.

Once you’ve begun auditing the wildlife in your yard, you’re almost guaranteed to feel a deeper connection to your land and the things living there. Hopefully, your observations and discoveries will also inspire you to do more to encourage biodiversity.

Laura Fenton is a home and garden writer with a special interest in the intersection between our homes and sustainability; she is the author of the weekly newsletter Living Small and The Little Book of Living Small.