Most ecological gardeners want to do what they can to save the earth. Dozens of groups across the country are doing so—quite literally—filling freezers full of native plant seeds. These critical repositories hold the future of our botanical past. With 40 percent of the plant species in the world under threat and at risk of extinction due to habitat loss, climate change, drought, extreme storms, and wildfires, native seed banks are vital to supporting our ecosystem and biodiversity. “As plant species increasingly face an uncertain future, seed banks are a way to hold that diversity and have it at our fingertips to use in the future,” says Kayri Havens, Chief Scientist and Negaunee Vice President of Science at the Chicago Botanic Garden. “They’re an insurance policy against catastrophic collapse,” says Tim Johnson, CEO of the Native Plant Trust.

To populate the seed banks, scientists and specially trained volunteers seek out rare and endangered species. They prioritize collecting from areas where plants grow naturally. “Plants, because they’re rooted in place over time, become locally adapted to our climate, our soils, the pollinators that visit them,” says Havens. “We want to capture that genetic diversity.” Scientists then monitor the plants, take photos for verification, and in some instances collect species for herbaria (a collection of pressed, dried plants for scientific study). Then when the time is right, they carefully collect seeds—always with proper permits and always abiding by strict conservation protocols to avoid pushing an endangered species further toward the brink.

On a 2019 collecting trip in the Ord Mountains, Cheryl Birker gathers seeds of Boyd’s monardella (Monardella boydii), a very narrow endemic found in only three populations in California’s Ord and Rodman Mountains of the Mojave Desert. Photo by Senior Conservation Botanist, Duncan Bell.

After collecting, the seeds are completely dried and stored in freezers, preferably in multiple locations to back up the backup, much the way computer data is stored. Recalcitrant seeds—those, like oaks and trilliums, that are unable to withstand freezing because of their high oil and protein contents—must be kept moist and use different methods of conservation.

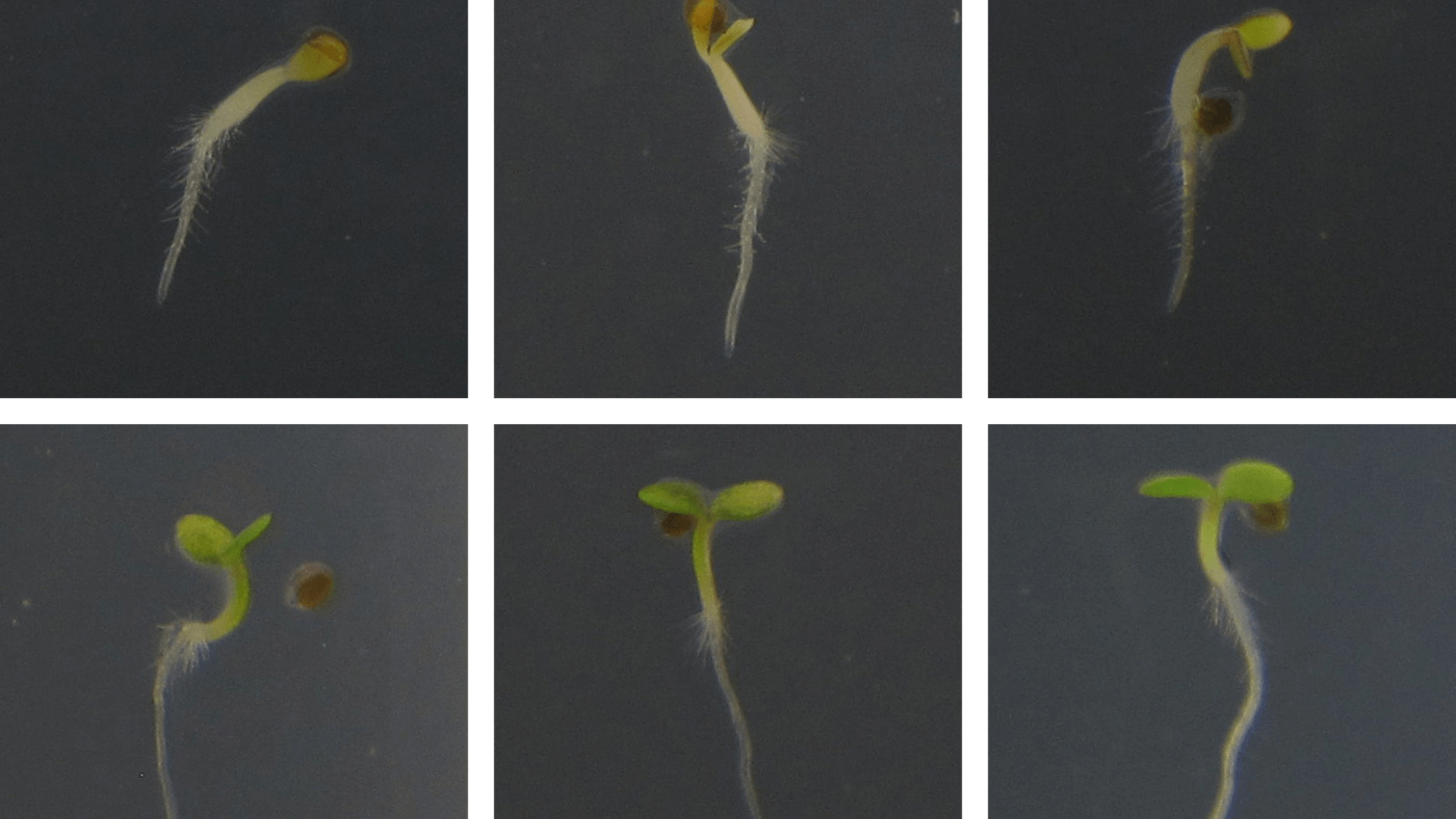

But it doesn’t stop there. “It’s important to conduct germination tests on stored seed in order to monitor viability over time and also to determine methods for breaking seed dormancy,” says Cheryl Birker, the Seed Conservation Program Manager at the California Botanic Garden. “If the intended use of these seed collections is to save a plant species from the brink of extinction, we’re going to need to ensure our seeds are staying alive in storage, and we’re going to need to know how to grow these plants from seed.” They also use these seeds to repopulate areas and grow the native seed population.

Birker, Havens, and Johnson tell us about their native seed banks—and share tips for home gardeners who want to help support biodiversity.

California Botanic Garden

Based in Claremont, CA, the California Botanic Garden is the largest seed bank dedicated to conserving California’s extensive native flora. “California is a biodiversity hotspot,” says Birker. “We have over 6500 native plant taxa; a third of those occur nowhere else in the world.” The team partners with other nonprofits and government agencies, such as the Federal Bureau of Land Management and the US Forest Service, to prioritize the “rarest and most threatened” plants. One example is the Hidden Lake Blue Curls (Trichostema austromontanum ssp. compactum). This tiny, native, and extremely rare plant features “cute little purple flowers and leaves that smell like vinegar,” and grows near a vernal lake in the San Jacinto mountains. Thanks to conservation efforts from their partners, which include moving a hiking trail away from the area where it grows, scientists were able to collect seeds and do surveys to figure out what the trends are for this plant. “We now have enough seed stored in the seed bank to support future reintroduction and we have also done several germination trials to determine the best method for growing the plants,” says Birker.

A glimpse inside a California Seed Bank freezer, which is housed at the California Botanic Garden and holds envelopes of seeds like this 2022 collection of scrub lotus (Acmispon argyraeus var. multicaulis). Photo by Cheryl Birker.

Chicago Botanic Garden

The Chicago Botanic Garden seed bank collects native plants from 15 Upper Midwest states, including Illinois, Ohio, and Kentucky. They collect “critically rare species as well as the 550 or so species that are most commonly used in restoration,” says Havens. Staff do most of the collecting in forest preserve districts, state and federal land, as well as on private properties. “One of the most fun projects we’ve worked on recently is in the Calumet area of Chicago that was impacted by the dumping of slag, a byproduct of the steel industry,” says Havens. “Ironically it creates a landscape that’s really similar to dolomite prairie, which is one of the most endangered ecosystems in the world.” The team planted the lakeside daisy, an endangered plant there, and it’s doing well. “It’s amazing when you take a site that you think is kind of hopeless, and have it play a really important role in conservation,” she says.

Chicago Botanic Garden staff, along with knowledgeable contractors, collect seeds from wild populations of native plants across the Midwest. Native seeds are dried at 15% relative humidity for at least three weeks to prepare them for storage. Photo courtesy of Chicago Botanic Garden.

Native Plant Trust

With two facilities in Massachusetts—Garden in the Woods and Nasami Farm—Native Plant Trust focuses on species endemic to the Northeast, with priority given to rare species. The bank currently stores more than 10 million seeds. “Our native plants often have complex dormancy mechanisms. We may not know how to germinate all of them, so the first step is to collect seeds,” says Johnson. “The second step is to figure out how to germinate them. Lastly, and perhaps the most important, is to make sure these populations are secure in the wild so we don’t need the seed banks down the road.” Last year, Native Plant Trust worked with a sundial lupine (Lupinus perennis) population in Vermont. This native lupine is a host plant for the endangered Karner blue butterfly. After noticing that the population in this area in Vermont was in decline, they were able to repopulate it from seed stored at Native Plant Trust decades earlier. They’ll return next year to see what the success rate is. “The genetics should just knit back together as if it was just a banner year for the plants to be producing babies,” says Johnson.

Inside Native Plant Trust’s rare plant seed cooler, one of several repositories that make up the rare plant seed bank. Alexis Doshas © Native Plant Trust.

What can gardeners do?

Grow native plants.

Birker, Havens, and Johnson all agree that gardeners should grow native plants at home. “Habitat loss and habitat fragmentation is the number one threat to native plants,” says Johnson. “When you grow native plants in your yard, you’re providing habitat and that habitat can become suitable for rare plants.” And please be sure to avoid all pesticides, even organic ones, which kill bees, butterflies, and other insects that most native plants depend upon to survive.

“Native landscapes sequester more carbon and benefit insects, birds, and other wildlife,” says Havens. “Plus, they avoid contributing to the problem of invasive species, which is one of the largest threats to native plant ecosystems in our region.”

Jesup’s milk-vetch (Astragalus robbinsii var. jesupii), a globally rare species grows in only three places in the world: a 16-mile stretch of the Connecticut River in Vermont and New Hampshire, where it inhabits thin pockets of soil deposited on the rugged ledges of the riverbank. Intensive monitoring, led by Native Plant Trust’s Conservation staff, began in the late 1990s. In 1986, when botanists first collected seeds of Jesup’s milk-vetch to bank, the field records do not mention any invasive plants sharing its habitat. Today, several grow in its habitat. With their partners, they are removing invasives plants, augmenting existing populations, and introducing plants on sites that appear to contain suitable habitat. Here, this seedling, grown in Native Plant Trust’s native plant nursery at Nasami Farm in western Massachusetts, was transplanted on site. Lea Johnson © Native Plant Trust.

Enjoy nature responsibly and use iNaturalist.

Botanists benefit from community science apps like iNaturalist. Birker notes that she and her colleagues might notice a person posting photos on the app of plants they are targeting for seed collection in bloom. They’ll know that they’ll have to get out there soon to collect. While you’re out in nature, it’s crucial to stay on paths to avoid trampling on plants to snap a photo and never, ever collect from the wild. Leave that to the professionals.

Give back to your local native seed bank.

It’s a race against the clock. Help these important institutions financially, sign up to volunteer where you could get trained to help out on projects like seed cleaning, and make your support for native plants known. It’s especially important today, when the current administration is reducing funding and protections for national parks and preserves and conservation. “Talk to your local politicians and voice your concern,” recommends Birker. “And support local nonprofits and organizations doing this work.”

An upclose look at Krantz’s Catchfly (Silene krantzii) seeds, another narrow endemic only known from a handful of populations near San Gorgonio Mountain, the highest peak in southern California. Photo by Cheryl Birker.

by Melissa Ozawa

This is part of a series with Gardenista, which ran on January 23, 2026.