by Laura Fenton

Whether you call it a habitat hedge, wildlife thicket, pocket forest, or bio hedge, a border of native shrubs is a valuable addition to your garden. Here’s why.

Hedges are not usually a particularly exciting part of the garden. Whether you have a clipped privet hedge (which we hope you don’t!) or a row of tightly-planted arborvitae–hedges are most often a monoculture of plants installed for privacy and screening—a solid wall of uniform green—but what if they could be something more?

That was the question Ethan Kauffman, head gardener at the natural garden Stoneleigh in Villanova, PA, asked himself when considering how to replace a tired hedge that had previously divided an old tennis court from another part of the garden. Kauffman wanted to visually separate the two spaces with shrubs, but he and his team quickly realized they wanted to do something more interesting than a single-species hedge. “The more we thought about it, the more we talked about it, we just were like, why not experiment?” he recalls. (Read more about Stoneleigh here.)

The habitat hedge at Stoneleigh is shorn to 8-feet tall to create a formal hedge shape. Photograph by Samantha Nestory.

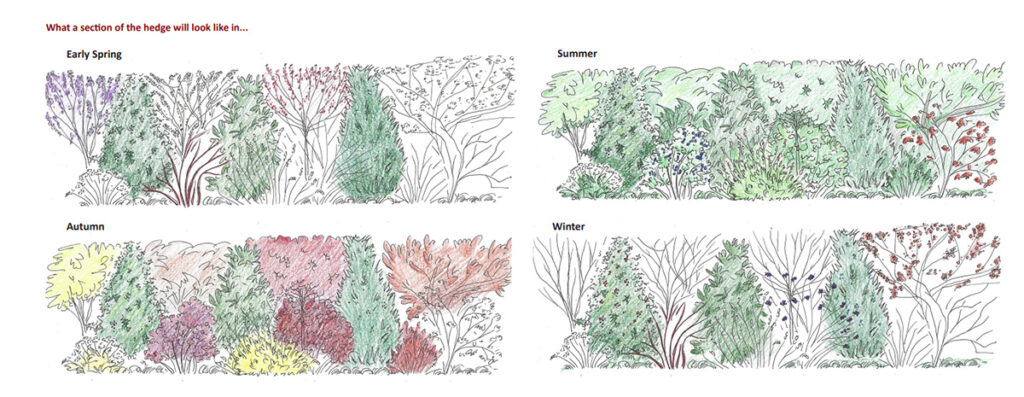

At first they considered using three to five different woody plants, but as they discussed the wildlife benefits of each species, they realized they wanted to do more. They ended up with a list of more than 60 woody plants laid out in two rows. The plant placement is designed with evergreen plants alternating on either side, so if there’s a deciduous plant on one side, there’s an evergreen opposite it, for screening in all seasons. Plants were chosen based on three factors: wildlife value, sun and shade tolerance, and texture. “We wanted it to be legible,” says Kauffman. “We did have a lot of one-off plants, but for some of our core plants like Magnolia Grandiflora or IIex opaca, we did threes and fives so that the hedge has some design intent.” Once the plants reached 8-feet, Stoneleigh’s gardeners sheared the top and shaped them into a formal hedge.

Kauffman points out a mixed hedge of native plants is not just beneficial to wildlife: It’s also more resilient. As our founder Edwina von Gal likes to remind gardeners: Nature does not like monocultures. If a pest or disease attacks a particular plant, you can lose a whole hedge in one fell swoop, something arborist Basil Camu, a co-owner of Leaf & Limb in Raleigh, North Carolina and the author of From Wasteland to Wonder, has seen firsthand. “If there is something that comes and attacks, say, a Leyland cypress hedge, which has happened (we have at least three or four different diseases that kill this species). Then, you’re left with a bare row of dead trees,” he explains. Seeing this was part of what inspired Camu to start advocating for what he calls a thicket or pocket forest. Leaf & Limb’s method is to lay down cardboard with six inches of arborists’ wood chips on top, then let it rot for about four months. Then in the dormant season, they plant the mulched area up with young native shrub saplings, keeping everything about two to three feet apart and limiting the plant palette to ones that grow no taller than about 20-feet.

It’s a lot more powerful in many ways—visually,

ecologically, resilience-wise. —Margaret Roach

Camu says that among his clients people who care about the well-being of Earth or birds and insects are the minority. “The big sell for most people is that using these native saplings to form a thicket has much lower costs on maintenance, so there’s a money savings and a time savings,” he explains. “The other thing that people really love is how fast these systems grow because when you plant lots of different species together they all benefit and grow faster.” After three years, the tiny saplings will have formed a full, naturalistic-looking privacy screen when in leaf; Camu notes that the trunks, branches and stems also provide some screening in the off-season.

A pocket forest planted by Leaf & Limb in its first growing season. The landscape stakes help make it clear what to weed and what to leave. Photograph courtesy of Leaf & Limb

The same pocket forest shot from the same spot in its third year. Photograph courtesy of Leaf & Limb.

Kauffman and Camu are not the only garden pros reconsidering what a “hedge” can be. Years ago, garden writer Margaret Roach of A Way to Garden and her longtime collaborator Ken Druse, coined the term “bio hedge” for the woody shrub borders like the one Roach has created for her own garden. Roach began by planting the perimeter of her property with winter berries to attract birds, but over the years, she added viburnums, chokeberries, aronias, and some conifers. The results are 20-foot deep beds coming in from the property line. “They serve as a hedge, but nothing is the same,” explains Roach. “It’s not all the same height, and they’re not pruned into a form like a formal hedge–they are undulating.”

Roach points out that increasing the variety of plants does more than just add visual variety. “Depending on how you plan it, this added shrubby layer or edge habitat can offer more diverse resources at different times of year,” she says “It’s a lot more powerful in many ways—visually, ecologically, resilience-wise.” Roach would like to see more people planting wildlife hedges. “People think the only option when they reduce their lawn is to replace it with meadow, but in fact, the woody plants are much lower maintenance,” she says. “If you tear up some of your lawn and transition it to a bio hedge (or whatever we want to call it), you’re going to get more privacy, more sense of enclosure, more bird habitat compared to just herbaceous plants down on the ground.”

So, if you’re planning a hedge for your garden, ask yourself what more it can be. But be patient. Whether you follow Camu’s lead and start with saplings for a wilder-looking thicket, Kauffman’s approach using more mature plants to form a formal hedge, or Roach’s deep-bed borders, it will take a couple years before your wildlife hedge reaches its full potential.

Laura Fenton is a home and garden writer with a special interest in the intersection between our homes and sustainability; she is the author of the weekly newsletter Living Small and The Little Book of Living Small.