Not far from the Brooklyn waterfront, the Naval Cemetery Landscape (NCL) is both a memorial to the dead and a haven for the living, teeming with lush native plants and countless birds and pollinators. “By purposefully bringing in life through an abundance of plants to a space that memorializes the dead, the landscape honors the cycles of life,” says Avvah Rossi, the landscape’s Director of Horticulture and Greenway Stewardship.

The land has had many lives over the centuries: It was once fertile farmland with fruit orchards and vegetable plots. Then, it spent the next 150 years at the service of the military, housing a naval yard, hospital, and cemetery where thousands of bodies rested before being mostly relocated in the early 20th century. The site later sported a recreational space equipped with a ballfield and hiking trails. When the land was decommissioned by the Navy in the 1990s, the city discovered that hundreds of bodies still remained buried in the earth there. In 2016, Brooklyn Greenway Initiative, the nonprofit that operates and manages the NCL, hired the landscape architecture firm Nelson Byrd Woltz to transform the land into a public place that honors the dead and the land’s rich history. Today, it also serves as a place of respite and grounding for the community and anyone using the adjacent Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway.

At the heart of the landscape is a 1.8-acre meadow that abounds with more than 50 different native plant species, including milkweed, asters, switchgrass, and bee balm—all selected to support bees, butterflies, moths, birds, and other wildlife. Tree snags stand on the perimeter, providing habitat. A wooden boardwalk meanders through the meadow echoing the path of the Wallabout Creek that once ran freely through the area. The Brooklyn Greenway Initiative maintains the garden sustainably, seeking to restore the land as they care for it. “We aim to layer the ecological needs of the landscape wherever we can by mimicking nature as much as possible,” says Rossi.

In mid-summer, yellow woodland sunflower (Helianthus divaricatus) and ten-petal sunflower (Helianthus decapetalus), wild bergamot (Monarda fistulosa), and common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) bloom in abundance, courting pollinators. Photo courtesy of Naval Cemetery Landscape.

Writer and photographer Ngoc Minh Ngo writes about visiting the landscape in her book New York Green, “You slacken your pace. You hear the birds. You see the insects. You pay attention to the green life that’s all around you, learning the names of the park’s flora and fauna, perhaps for the first time. The world reveals itself in a whole new language. Spend some time in this place and it might change your way of thinking.” (Read an interview with Ngoc Minh Ngo about her book New York Green in Gardenista.)

Below, Rossi shares how she and her team care for the garden in winter by minimizing the impact on the land and maximizing the benefits to the ecosystem.

1. Cutback Perennial Stems.

To maintain the meadow, Rossi and her team cut back swathes in late winter, though “the timing is getting earlier and earlier because of the warmer weather,” she says. They make sure not to cut the perennial stems too short, keeping them at 18 to 24 inches high to protect any pollinators that might be overwintering in the stems. While they’re doing this, they also remove annual weeds like bedstraw, which can start germinating as early as January, with a hoe. “Don’t worry about lightly hoeing around tough perennials like sunflowers and asters when they are dormant,” says Rossi. “You’re not going to kill them.”

“Milkweed plants are a pleasure to observe from the boardwalk in multiple seasons,” says Rossi, who leaves the seed heads up until late March. The garden is a certified monarch way station through the Monarch Watch program. Here, milkweed seed pods open in the fall among native switchgrass (Panicum virgatum). Photo by Ngoc Minh Ngo.

2. Build Up a Habitat Perimeter.

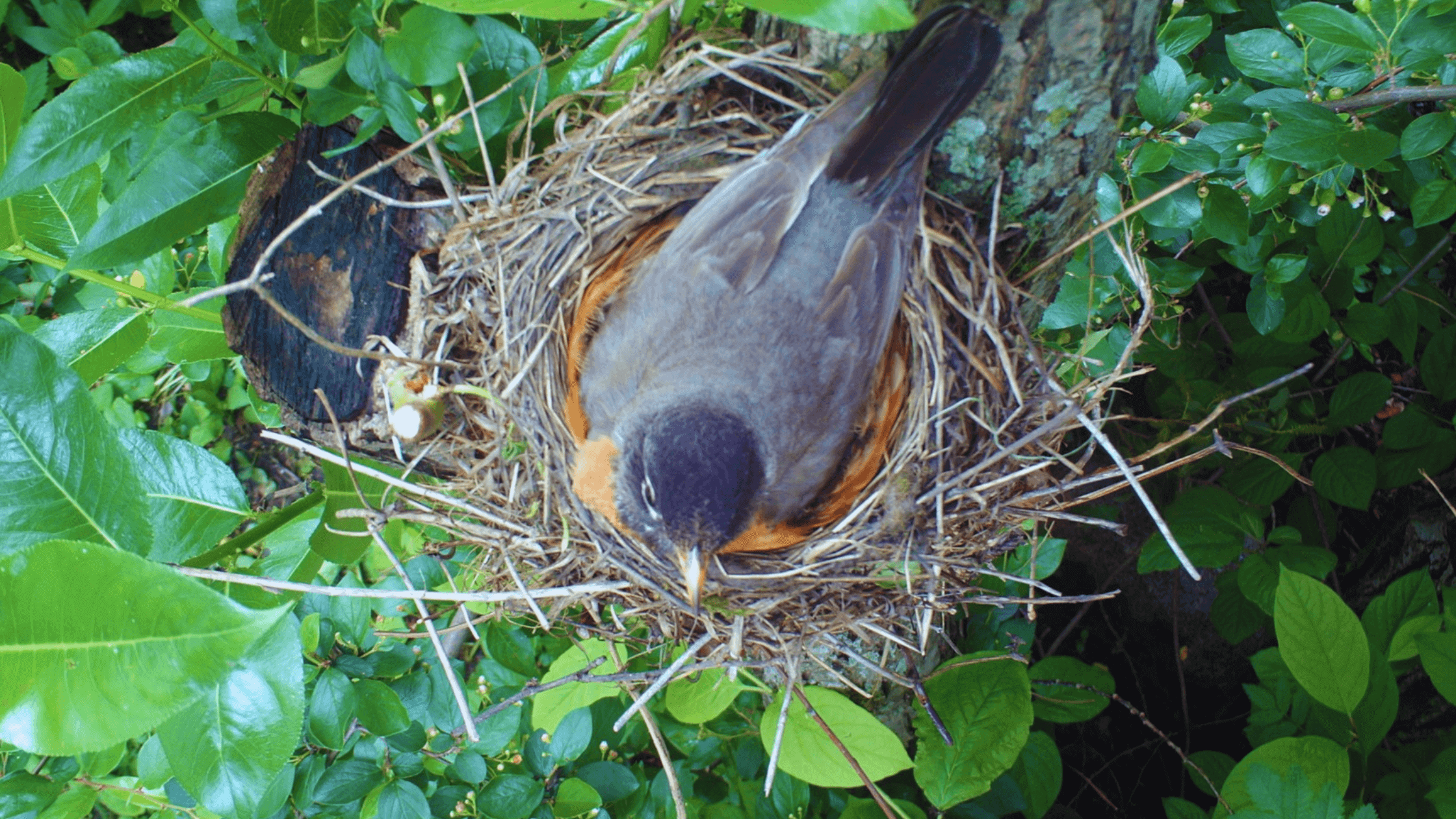

Throughout the year, the gardeners move natural debris, like large branches and stems, to the perimeter of the property instead of putting them in the trash or compost, to maximize the benefit to wildlife who use it for habitat. After the meadow cutbacks, they bundle the clippings together and stack them vertically against the back fence. “It’s important to keep the stems intact to protect any bees, like the small native carpenter and leafcutter, that might be overwintering in the stems,” says Rossi. If they left the cut stems on the ground, they could get waterlogged or crushed, which could harm the insects inside. The gardeners also leave snags (dead trees) along the perimeter for birds, like woodpeckers, hawks, and flycatchers, to use. “All this material becomes nesting and hunting habitat for birds, shelter for small mammals, and homes for insects” says Rossi. Eventually, it will all break down and enrich the soil—and the cycle will continue.

A Cooper’s Hawk perches atop a tree snag, which has been left on the perimeter. The gardeners also leave dead lower branches of a pin oak to provide hunting perches for smaller insect-dependent birds that shelter and hunt from border zones of woodland and meadow, says Rossi. Photo courtesy of Naval Cemetery Landscape.

3. Look Out for Invasives.

The NCL gardeners use only manual methods to remove invasive species. Most natives go dormant in winter, but many nonnative species like English ivy or nonnative grasses, such as orchard grass, either stay green or pop up early so they’re easy to spot in the winter landscape. It’s an ideal time to get rid of them while they’re highly visible. Here’s how they tackle the different types of invasives on site in the winter.

Clearing away evergreen English ivy (Hedera helix) is a priority in winter for the gardeners, who are methodical about removing all the roots when they see it. They then place the rolled-up ivy in the fork of a dead tree, like this downed mulberry, which has been left there as habitat, to dry out. Ivy as short as three inches has been shown to regenerate if left in the landscape or put into colder compost piles. Photo courtesy of Naval Cemetery Landscape.

Herbaceous plants

“It’s easy to spot evergreen English ivy in the winter,” says Rossi. “We’ll pull it out and remove the roots, ball it up, and let it totally dry out in the fork or crotch of a dead tree.” (You can also dry out the vine in a garage or shed.) Since English ivy can root in soil if any part remains alive, you need to make sure the clippings are completely dried out before composting them. You’ll know it’s ready to compost, when the vine feels brittle to the touch, says Rossi.

Woody plants

The team walks the area and tags invasive shrubs like multiflora rose and buckthorn. They’ll cut down buckthorn to the ground and cover it with non-light penetrating fabric or plastic to prevent photosynthesis from occurring. With multiflora rose, which is more aggressive, they may have to cut back the shrub four to five more times over the season for a couple of years to eradicate it or remove the entire root ball with a weed wrench tool.

NCL is a peaceful, meditative memorial landscape run by the Brooklyn Greenway Initiative (BGI), which showcases and champions the potential impact of the Green in Greenways—corridors for cyclists and pedestrians that ideally provide separation from car lanes and feature street trees and/or native plantings. The organization also provides public programming that enhances connections to nature for the community. In the winter, visitors can see the historic Naval Hospital through the bare, deciduous trees beyond the meadow. Nature Sacred designated the NCL as one of its only two Sacred Spaces in New York City. Photo courtesy of Naval Cemetery Landscape.

Grasses

Winter is an excellent time to remove unwanted cool season grasses, like orchard grass, because they come up earlier than native warm season ones. Orchard grass is easily identified by its distinct color, unique ligules, and flattened or keeled leaves that are also folded around the bud so that they resemble iris foliage when they emerge from the ground. The gardeners will pop out small clumps of it with a soil knife. In larger areas, they’ll shave the root ball instead of removing the entire plant. “This year, we’re also going to try to use a weed whacker in dense areas of other cool season grasses, scalp the earth, and then plant with native seeds to see what will take root,” Rossi says.

The Naval Cemetery Landscape is open year-round, with limited hours in winter. The organization develops programs aimed at building skill sets for urban visitors with an emphasis on nature education and mental wellness activities. To learn more, visit their website.

By Melissa Ozawa

This is part of a series with Gardenista, which ran on January 23, 2025.